TPO Magazine - Posted by Nora Lough

May 17, 2023

After leaving active submarine duty in the U.S, Navy, Scott Goodinson worked on various jobs that included a couple of years pumping out portable restrooms.

One day while cleaning a restroom at a baseball field he turned off the vacuum truck and overheard a father say to his son, “That’s the kind of job you get if you don’t go to college.”

Hearing that snippet of conversation brought Goodinson to a pivot point. “My wife was pregnant with our second child,” he says. “Sucking out port-a-johns is considered one of those dirty jobs. It paid the bills, and I enjoyed doing it, but it was time to move on. I said to myself, ‘I’ve got to do something more with my life.’”

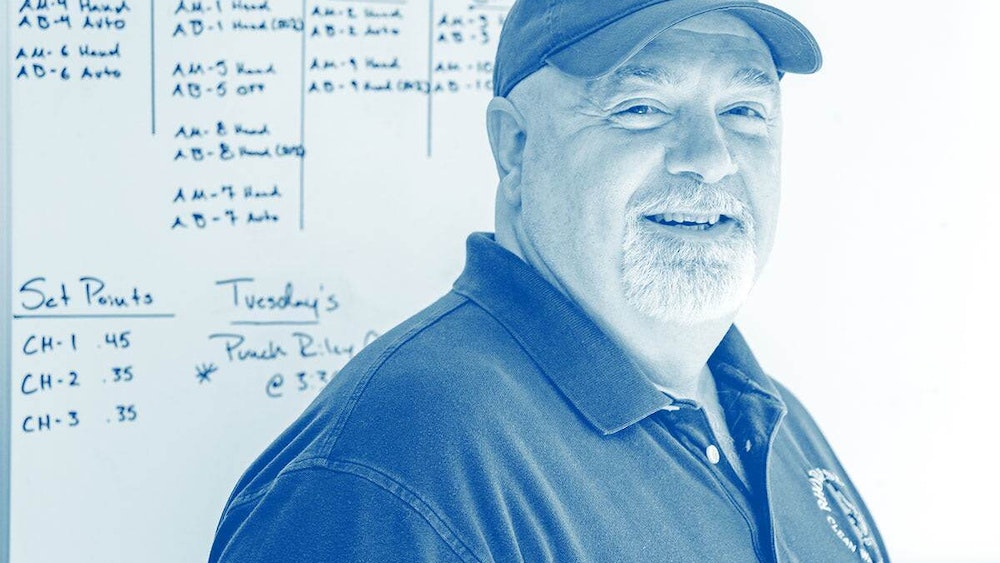

That something more turned out to be a long career in the clean-water profession. Goodinson, winner of a 2021 Operator Award from the New England Water Environment Association, is now superintendent of the Scarborough Water Pollution Control Facility in the Town of Narragansett, Rhode Island.

After 32 years in the industry working at four clean-water plants in his native Rhode Island, he feels he has found himself a home — a plant where he will be glad to stay until he retires.

COOKING FOR THE CREW

While attending high school in Warwick, Rhode Island, Goodinson worked part time at restaurants and bakeries and dreamed of owning a restaurant someday. To pursue his love of cooking, he dropped out of high school in April of his junior year, at age 17, to join the Navy.

After boot camp he went through Mess Specialist school in San Diego, followed by submarine training in Groton, Connecticut. He was assigned to the USS Tinosa, a nuclear fast-attack submarine, as the chef.

While in the Navy he earned his GED. He left active duty after four years at the rank of petty officer second class, transitioned to the reserves, and returned to Rhode Island. Unsure of a career direction, he took an assortment of jobs.

While working for the portable restroom company, he learned of an opening at the Cranston Water Pollution Control Facility and was hired in 1990 as an operator in training. During 20 years at that facility (20.2 mgd design), operated by the environmental services company that is now Veolia, he advanced to operator, chief operator and, ultimately, operations manager.

His next stop was at the West Warwick Regional Water Pollution Control Facility (7.9 mgd), first as assistant superintendent and then superintendent. In 2012 he joined the team at the Warwick Sewer Authority treatment plant (7.7 mgd), staying seven years, the last five as superintendent. He assumed his current position in November 2019.

A PERFECT FIT

“I took a small cut in pay to come here,” Goodinson says. “It was well worth it, when you’re pushing 60 years old you want to change things up a bit. Sometimes the stress isn’t worth the money. It’s a smaller plant with a less challenging permit. It’s not an easy plant to run, but it’s manageable. It has beautiful views. I’m really happy here.”

The coastal Town of Narragansett attracts tourists for its beaches. The population of 16,000 doubles in summer, and so does the flow of the treatment plant (1.4 mgd design, 0.6 to 0.7 mgd average). Influent first passes through a Raptor fine screen (Lakeside Equipment) and a lift screw grit-removal system (Keene Corporation).

Three centrifugal lift pumps (Grundfos) deliver the flow to an oxidation ditch with three trains. In 2018, paddle wheel aerators were replaced with 10 floating aerator mixers (Newterra). The flow then passes to two secondary clarifiers, followed by chlorine disinfection, dechlorination with sodium bisulfite, and discharge through a diffuser 2,200 feet offshore in Rhode Island Sound.

Biosolids are thickened to about 3.5% solids and hauled to a Synagro facility in Woonsocket for dewatering and incineration.

COHESIVE TEAM

The plant’s straightforward permit requires 30 mg/L BOD and TSS. Keeping compliant is the job of Ken McKay, process control and pretreatment coordinator; Phil Rattenni, maintenance supervisor; Dan Johnson, foreman; and operators Steven Card, Jake Mambro, Riley Greene and Chad Cota. “We are all cross-trained and switch duties as needed,” Goodinson observes.

Johnson and Mambro maintain the system’s 19 pump stations and flush the lines on a rotating basis, about one-fourth of the system per year. Greene, beyond his role as a plant operator, operates the CCTV sewer inspection system and is a member of the Rhode Island team in the Water Environment Federation Operations Challenge. Cota is responsible for solids handling and Card takes care of sampling, lab testing and process reporting.

“All team members have assigned planned maintenance tasks, do landscaping and handle any other work needed to keep the facility in tip-top shape and in compliance,” says Goodinson.

“Behind every successful superintendent is a good team,” Goodinson says. “We have a smaller facility with a smaller staff, and it’s intimate. We have team members who are not only on a first name basis but almost finish each other’s sentences. We really mesh, like a NASCAR pit crew.”

A regular challenge is dealing with the variability of flows from winter to summer. “Air is one of the key things, keeping the bugs happy,” Goodinson says. “Also keeping a close eye on the microscopic evaluations in the lab. We also monitor the secondary clarifier blankets and watch the filamentous organisms to determine whether we need to chlorinate the return activated sludge.”

KEYS TO LEADERSHIP

In leading his team, Goodinson draws on experience gained in previous jobs. He mentions one mentor in particular, Ernie Persechino with whom he worked for three years at Cranston. “I was the second shift chief operator. I would see him when I was coming to work at 3:30, and we would go over the previous night’s assignments.

“Maybe I had an issue, like I couldn’t find a certain valve. He had an old ruler, like a teacher who has a yardstick. He would take me by the hand and say, ‘Here’s the pump. Here’s where it starts. Now, follow that system. Put the end of the ruler on the pipe, follow it down, and trace out the system as best you can.’

“I learned so much from that guy. I would turn around and follow the processes, where they began and where they ended. In time I knew every single valve, every little loophole in that plant. That’s how you learn. You have to take ownership of the facility. When you buy in and take ownership, that’s how you go from being a good operator to an excellent operator.

“I’ve seen a lot of good bosses. I try to emulate them and pick up on the skills they use. I tell younger colleagues who are getting into leadership roles to lead by example, to be a person of integrity. I don’t like the word ‘subordinates.’ Your people are your team. They’re your co-workers. I try to show them that by the way I talk to them, by looking them in the eye and letting them know I appreciate them. People want to be spoken to like they matter.”

On the other hand, he doesn’t shy away from difficult conversations: “I’ve had some operators and mechanics who just needed some one-on-one training, someone willing to talk to them about their shortcomings and the improvements they needed to make. That can help you as a manager by heading off problems early, by counseling them, making it a teaching moment instead of a disciplinary moment.”

While fostering close relationships, he does draw some boundaries. For example, he doesn’t have lunch with his team members; he eats in his office: “If you’re eating with the guys and going out for drinks with the guys, they treat you like you’re one of the guys. And sometimes the respect level is lost.”

ACTIVE IN THE INDUSTRY

While helping his team members advance, Goodinson has grown by giving back to the industry in various ways. He is a graduate of the Rhode Island Interlocal Trust Supervisor’s Management Institution, which puts on boot camps to teach leadership skills. He’s also a graduate of the Veolia Water Project Manager’s Boot Camp.

He has earned a variety of train-the trainer certifications, has completed the 40-hour OSHA Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response course, and is trained in first aid and CPR. He has served as a board member and for a time vice chair of the Pawtuxet River Authority and Watershed Council, a consortium of five communities dedicated to protecting Rhode Island’s largest river.

He is perhaps most proud of his contributions to the Rhode Island Clean Water Association, where he has served as vice president, president, state director and now past president. The association is a training and resource center for the state’s operators.

“We offer operator training in microbiology, lockout/tagout, seal training, pump training and more,” he says. “It’s not just the training. It’s the networking and the camaraderie. We have an annual trade show where operators can meet the vendors. We offer scholarships from $500 to $3,000 for high school graduates.

“We have an annual holiday party. We do a food drive for the local food bank. We do an annual chowder cookoff here in our plant, and I’m glad to say I have three first-place awards on my wall. I make a mean chowder.” Goodinson strongly supports the Operations Challenge, and after some years as a Rhode Island team contestant he chaired the New England Water Environment Association Operations Challenge Committee in 2020-21.

For 2022, Goodinson was nominated as NEWEA vice president; he will be president in 2024.

CHALLENGES TO COME

Looking ahead, Goodinson is planning upgrades to the biosolids thickening process and the polymer and potassium permanganate feed systems, replacement backup generators and automatic transfer switches at the plant and several lift stations, and various building repairs.

“It’s a good town,” he says. “It’s well run. We have one of the lowest sewer rates in Rhode Island. The ratepayers are happy. This is a good place to finish out my career. Eight more years will bring me to 67. That’s my retirement age. If I’m still having fun, I’ll keep working.”

Meanwhile, Goodinson is proud of the role his profession plays in keeping the waters clean for fishing, swimming and boating. He notes specifically the improvement in the Pawtuxet River, his home stream. He also notes the work he and Rhode Island colleagues have done to help keep open the beaches that were often closed when he was young.

All in all, it has been an amazing journey for someone who describes himself as “just a humble ex-Navy cook.”